GPs’ perspectives regarding their sedentary behaviour and physical activity: a qualitative interview study

July 13, 2022

Congratulations to the 2022 SBRN Award Winners!

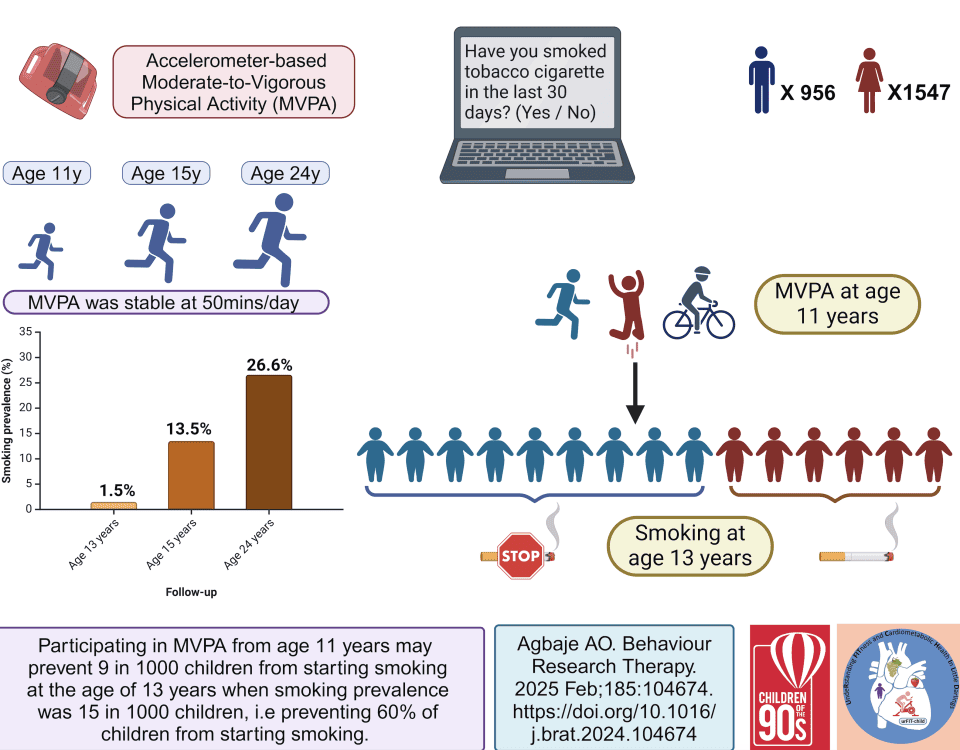

August 1, 2022Thank you to Dr. Wendell C. Taylor for providing this blog post. The post is summarizing his paper titled “Understanding Variations in the Health Consequences of Sedentary Behavior: A Taxonomy of Social Interaction, Novelty, Choice, and Cognition” which has recently been published in the Journal of Aging and Physical Activity (available here). More about the author can be found at the bottom of the post.

We tend to think that sedentary behaviors are detrimental, unhealthy, and likely to cause weight gain—think binge-watching your favorite television series for hours while stuffing your face with an entire bag of potato chips. However, such a negative scenario isn’t always the case, as shown in a recent study on the attributes of sedentary behavior (https://doi.org/10.1123/japa.2020-0360).

By definition, a sedentary behavior is any waking behavior performed in a sitting or reclining posture and characterized by low energy expenditure. Various behaviors can be classified as sedentary, and they can be either health-promoting or health-compromising.

For example, some sedentary behaviors (such as reading) are associated with favorable health outcomes, whereas other sedentary behaviors (such as television viewing) are associated with unfavorable health outcomes. What might account for this difference?

In my research on this topic, I was unable to find a published framework that could be used to explain these discrepant findings. Therefore, I developed Taylor’s Taxonomy of Sedentary Behaviors to rate, rank, and create a hierarchy of sedentary behaviors and health outcomes. Such a hierarchy enables the sedentary pursuits that promote mental health, psychological health, and well-being to be identified and understood in real-world settings.

Four domains

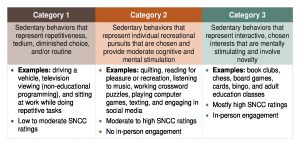

Taylor’s Taxonomy categorizes sedentary behaviors according to four domains, abbreviated SNCC:

- Social interaction – Does the activity promote social interaction, versus isolation?

- Novelty – Is the activity new or different?

- Choice – Is the activity one in which the participant can willingly engage, versus having little or no choice?

- Cognition – Is the activity mentally stimulating?

Taylor’s Taxonomy proposes three categories of sedentary behaviors, based on SNCC ratings:

What does it mean?

Context is key when rating a sedentary behavior. For example, consider driving a car. Generally speaking, driving is rated low on the SNCC scale because typically it is routine—not especially stimulating, novel, socially engaging, or even optional. However, driving in a blinding snowstorm would be rated differently on the SNCC scale, in terms of novelty and cognition (stimulation). Also, driving could be one’s only choice, or it could be one of many choices (bicycling, metro rail, city bus), depending on where one lives.

In stark contrast, in-person adult education classes are typically rated high on the SNCC scale: Participants choose to enroll in classes, they engage in in-person interactions with other students and the professor(s), and they learn new concepts and ideas that are cognitively stimulating.

With these points in mind, consider selecting sedentary behaviors that protect and enhance your health. In general, Taylor’s Taxonomy rates positive in-person interactions more favorably than positive non-face-to-face interactions:

- Category 3 sedentary behaviors will protect and enhance health to a greater extent than behaviors in Categories 1 and 2.

- Category 2 sedentary behaviors will protect and enhance health to a greater extent than behaviors in Category 1.

- Category 1 sedentary behaviors will confer the fewest health benefits.

Note that ratings on SNCC domains and sedentary behaviors may vary somewhat depending on the sub-population (e.g., gender, age, racial/ethnic identity), but the overall approach still applies.

Health outcomes

Categorizing sedentary behaviors according to Taylor’s Taxonomy can help identify activities that promote psychological and emotional health, including wellbeing, memory function, mental alertness, elevated mood, happiness, and joy. Constructive sedentary behaviors can even prevent or lessen the effects of depression, dementia, and cognitive decline. Other benefits include positive effects on blood pressure, stress hormone levels, and “feel good” brain chemicals such as endorphins and dopamine.

Summary

In the study of sedentary behaviors, a long-held assumption is that all sedentary behaviors yield unhealthy effects because the person is not physically active. The basic premise of Taylor’s Taxonomy of Sedentary Behaviors is that not all sedentary behaviors are the same, nor are they all necessarily bad. I developed Taylor’s Taxonomy as a way to identify the health outcomes associated with various sedentary behaviors. My hope is to encourage health-promoting sedentary behaviors and discourage health-compromising sedentary behaviors to enhance the wellbeing and health of all communities.

What are your thoughts about sedentary behaviors? Did this post change any of your views? Tell me about it in the comments below.

References

de Rezende, L.F.M., Rey-López, J.P., Matsudo, V.K.R., & do Carmo Luiz, O. (2014). Sedentary behavior and health outcomes among older adults: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 14(1), 1–9.

Taylor, W. C. (2021). Understanding variations in the health consequences of sedentary behavior: A taxonomy of social interaction, novelty, choice, and cognition. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity, 30(1), 153-161. DOI: 10.1123/japa.2020-0360 PMID: 34257158.

Taylor, W. C., Rix, K., Gibson, A., & Paxton, R. J. (2020). Sedentary behavior and health outcomes in older adults: A systematic review. AIMS Medical Science, 7(1), 10-39.

All images courtesy of pixabay.com. Dr. Taylor thanks Jeanie Woodruff, BS, ELS, for her contributions to the writing of this post. Also, Dr. Taylor is grateful to Karen L. Pepkin, MA, for her revisions to the blog post.

About the author

Wendell C. Taylor, PhD, MPH, has more than 30 years of experience in academia as a university professor. His research expertise includes sedentary behavior, physical activity, workplace health promotion, health equity, and environmental justice. In addition to authoring Taylor’s Taxonomy of Sedentary Behaviors, Dr. Taylor is the architect of Booster Breaks in the Workplace, Healthy Weight Disparity Index, and Ethical Hiring Policies for People Who Smoke.

Dr. Taylor was the principal investigator of a National Institutes of Health grant entitled, “Booster Breaks: A 21st Century Innovation to Improve Worker Health and Productivity.” This study was a cluster-randomized controlled trial of health-promoting breaks in the workplace and assessed physical, psychological, and organizational-level outcomes.

Dr. Taylor is committed to improving access to physical activity opportunities and promoting healthy sedentary behaviors for all communities.