Measurement of sedentary behaviour in human adults: A toolkit

January 13, 2021

Genetic variants related to physical activity or sedentary behaviour: a systematic review

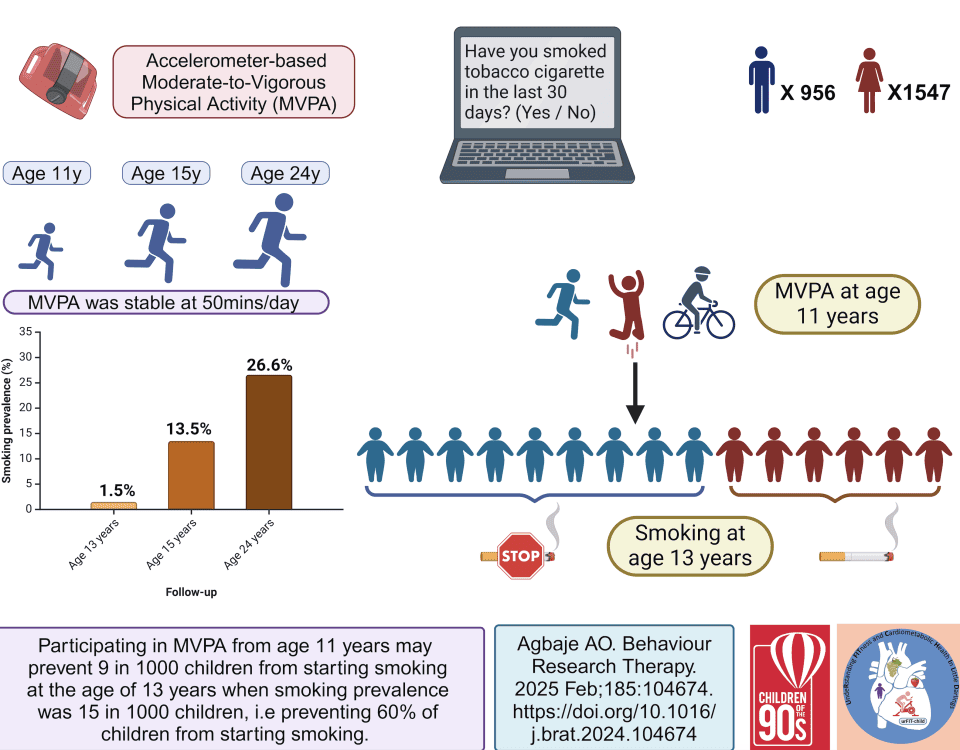

January 27, 2021Thank you to Dr. Trish Tucker and Julie Statler for providing this post. The blog post describes a study titled “Habitual physical activity levels and sedentary time of children in different childcare arrangements from a nationally representative sample of Canadian preschoolers” that was recently published in the Journal of Sport and Health Science (available here).

Background

Childcare refers primarily to center-based and home-based facilities that offer group-based care outside of a child’s home. Approximately 80% of Canadian preschoolers (age 3-5 years) attend childcare facilities (1) and they spend many hours (at least 30 hours per week) in these venues (2). Therefore, the childcare environment has been identified as an optimal setting to support the physical activity and sedentary time behaviour patterns of young Canadian children.

Little is known about how different childcare types influence the habitual or daily activity levels of young children. Traditionally, parents have believed that children experience high levels of activity throughout the day (3). Are parents correct in this assumption? Does this lead to lower levels of activity at home because parents believe their child was active while in childcare? Varying regulations across childcare types and centers influence the amount of activity children actually experience and the amount of time they are sedentary (4). In addition, how do parental activity habits influence a child’s activity levels? What impact does this have on children who stay at home with a parent or caregiver rather than attending traditional childcare? These are some of the questions we sought to better understand.

What did we do?

To date, research exploring the habitual levels of physical activity and sedentary time among preschoolers in childcare has only been conducted on a small scale and during childcare hours. The purpose of our study was to explore physical activity levels and sedentary time among Canadian preschoolers who receive childcare in a variety of settings. A secondary objective was to explore differences in physical activity and sedentary time in boys and girls, separately. Using data from the Canadian Health Measures Survey (CHMS), which is conducted by Statistics Canada, this survey gathers information on Canadians’ health and health habits. As part of the CHMS, participants wear Actical accelerometers to gather physical activity and sedentary time data. One advantage of using this dataset was that it provided a nationally representative sample of Canadian preschoolers.

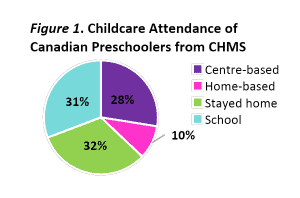

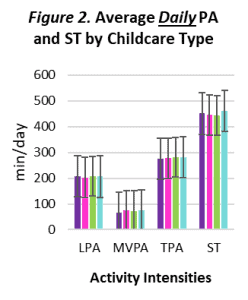

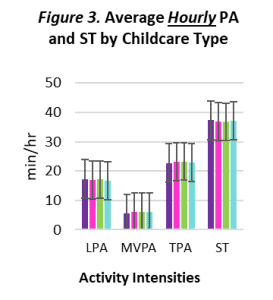

To be included in the study, participants had to meet the following criteria: (a) be between the ages of 3 and 5 years, (b) had 3 or more valid days of accelerometer data, and (c) enrolled in one of 4 types of childcare exclusively (i.e., [1] centre-based daycare, nursery school or preschool; [2] home-based daycare; [3] school, including kindergarten; [4] stayed at home with a parent or caregiver). A total of 650 participants (Figure 1) met our inclusion criteria. Average daily and hourly rates of activity were calculated for the following levels: light physical activity, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, total physical activity, and sedentary time.

What did we find?

No significant differences were observed for the full sample, or in boys or girls separately, for daily (Figure 2) or hourly (Figure 3) rates of each activity level. For both daily and hourly rates of activity, boys had the most moderate-to-vigorous activity and total activity in school, whereas girls had the most moderate-to-vigorous activity in home-based settings. For daily rates of activity, both boys and girls had the most sedentary time at school. For hourly rates of activity, boys had the most sedentary time in center-based childcare, whereas girls were still most sedentary at school. Hourly rates of activity may provide a more accurate picture of activity since it accounts for the participant’s wear time of the accelerometer. Our results suggest that physical activity and sedentary time for children enrolled in childcare and kindergarten do not differ from those who stay at home. In addition, we found that activity levels did not vary significantly by gender in different childcare settings.

Previous research had led us to hypothesize that children in center-based childcare would be significantly less active and more sedentary than those in other childcare settings; however that was not supported. A few limitations have been identified which may have contributed to our results. The geographic origin of our participants was unknown. Since each province has differing childcare policies regarding physical activity, childcare venues included in the same category may have followed different standards, skewing the data. In addition, participants began recording physical activity data on different days. Therefore, it is possible that children’s accelerometer tracked weekend data for some and weekday data only for others. Since children do not typically attend childcare on weekend days, this may have contaminated the effect being explored in our study.

What’s next?

This is the first study of its kind to examine the influence of childcare status on activity behaviours among a representative sample of Canadian preschoolers. Additional research is needed to understand the impact of varying programming, policies, and environments across Canada, and their subsequent impact on preschooler’s daily activity levels. It will also be important to explore the impact of more than one childcare status (e.g., center-based and at home with a parent) on activity levels given the influence both parents and childcare providers have on young children’s activity affordances.

References

(1) Cleveland G. New evidence about child care in Canada: use patterns, affordability, and quality. IRPP Choices. Available at: http://on-irpp.org/ 2eoJRTC; 2008. [accessed 05.01.2018].

(2) Sinha M. Child care in Canada. Statistics Canada. Available at: www.stat can.gc.ca/pub/89-652-x/89-652-x2014005-eng.htm; 2014. [accessed 05.01.2018].

(3) Sallis JF, Patterson TL, McKenzie TL, Nader PR. Family variables and physical activity in preschool children. J Dev Behav Pediatr 1988;9: 57–61.

(4) Vanderloo LM, Tucker P. Physical activity and sedentary behavior legislation in Canadian childcare facilities: an update. BMC Public Health 2018;18:475. doi:10.1186/s12889-018-5292-1.

About the authors

Julie Statler received her Master of Science in Health & Rehabilitation Sciences from Western University (London, Canada) in 2018. She is passionate about making healthy living accessible for all. She is currently completing her practical training to become a Registered Dietitian.

Dr. Trish Tucker is an Associate Professor in the School of Occupational Therapy and the Director of the Child Health and Physical Activity Lab at Western University. Dr. Tucker’s expertise are in the broad areas of health promotion, physical activity, and child health. Her primary area of research is the measurement and promotion of physical activity with a particular focus on preschool-aged children.