Sedentary behaviour mechanisms: biological and behavioural pathways linking sitting to adverse health outcomes

April 6, 2018What is the best questionnaire to measure sedentary behaviour? “well, it depends…”

April 30, 2018Today’s post comes from Nathalie Berninger, a PhD Candidate in the Faculty of Psychology and Neuroscience at Maastricht University, where she describes work recently published in the online journal Sensors. The full study is available here.

Ms Berninger is employed by VitaBit to further validate the device and to develop a sedentary behavior intervention. However, apart from providing the devices and access to the software and the raw data for the current study, VitaBit had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

As you are here, you probably know that an unhealthy sitting pattern is detrimental for your health. The increased cardiovascular and metabolic risks are only partially compensable by regular work-outs. Despite, we sit down, and (sometimes would like to) never get up again. Almost everyone is at risk.

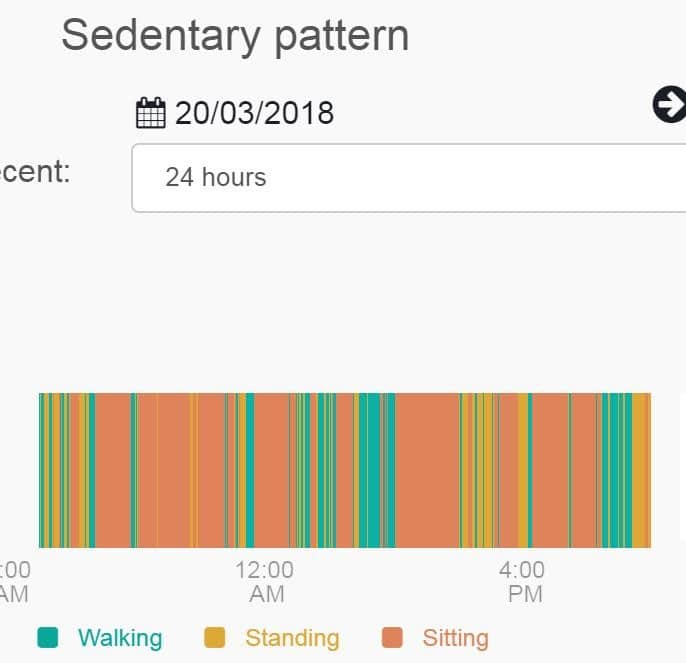

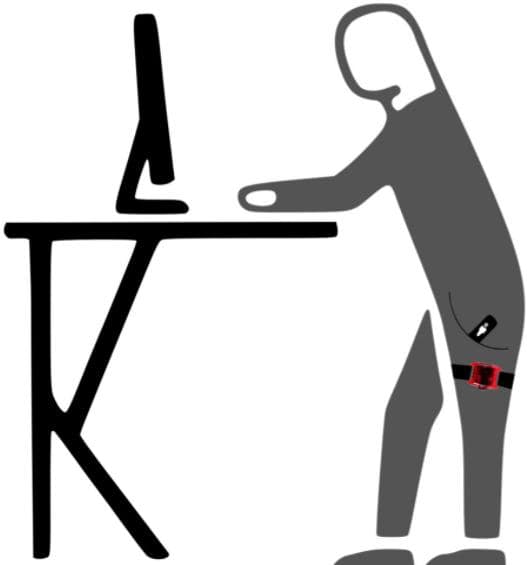

But our project is not about telling everyone that they will die if they continue staying comfortable. Instead, we were searching for the bright side of not sitting. Thus, the VitaBit team developed a toolkit: VitaBit. It includes a measurement tool (3.9 × 1.4 × 0.85 cm, 4.8 g, black, to be magnetically attached on the trousers), and ways to be rewarded by achieving self-set goals, winning challenges against others, or just seeing a colorful daily activity pattern when sitting time is regularly interrupted by standing or activity (see figure).

We also aimed for providing a tool for both, researchers (downloading anonymous activity data of their participants, who gave their consents before) as well as interventionists (seeing their participants’ data and individually providing tips and tricks through push-notifications or emails). In contrast to current best-practice devices, such as the ActiGraph, the raw data are already converted into the three modes sitting, standing and walking.

In a first study, we investigated whether the VitaBit device delivered what it promised, and conducted a validation study, trying to answer four questions:

- If I am sitting (standing, or walking), does my VitaBit also detect this as sitting?

= SENSITIVITY

- If I am not sitting, does my VitaBit also reward me by also indicating this as NOT sitting?

= SPECIFICITY

- If my VitaBit application, tells me that I was sitting 8 hours, how much was I indeed sitting?

= POSITIVE PREDICTIVE RATE

- If my VitaBit application, tells me that I was NOT sitting, how much was I indeed not sitting?

= NEGATIVE PREDICTIVE RATE

For this study, we asked 11 people to wear the VitaBit, and perform certain activities (sitting, standing, walking, sitting down and getting up in different speeds) while we observed them. Since in daily life the VitaBit measures everything, including accelerations and transitions between postures, we also challenged the device with very tight transition times between activities. Additionally, we told our participants to sit down or get up very slowly (e.g., 3 seconds) to see, if the VitaBit was still able to distinguish sitting from standing.

Additionally, seven volunteers wore the VitaBit together with the ActiGraph in daily life to measure their daily life activities, including ‘strange’ activities like active sitting, driving their car or driving their desk chair.

The ActiGraph is already frequently used in research, and has already been found to be a valid sitting detector.

Afterwards, we compared the VitaBit with direct observation and ActiGraph on a minute-by-minute basis. Besides calculating the four performance values mentioned above, we also compared activity distribution, i.e. sitting time observed vs. sitting time detected by the VitaBit.

In the laboratory setting, our results showed that 74.6% to 85.7% of all sitting and standing minutes were correctly detected by the VitaBit device. When not sitting or not standing, this was correctly identified in over 91.2% of all cases. And over 97.3% of all walking minutes were correctly detected. Those results were similarly to those from the ActiGraph.

During daily life activities, VitaBit agreed with the ActiGraph detection for over 72.6% of the minutes for sitting, when compared on a minute-by-minute basis. On average per day, the VitaBit indicated 444 (± 200) minutes of sitting, while, according to the ActiGraph, participants were sitting for 489 (± 171) minutes.

To conclude, the VitaBit is an end-user, researcher, and interventionist friendly product at low cost for objectively measuring sedentary behavior, and, in addition, we found that it performs similarly well as other best-practice devices.